Fall 2021 marks the tenth anniversary of adopting community-engaged projects in my graduate course, MPA 8600 - Effective Nonprofit Management, at Villanova University. Since their introduction to the course in Fall 2011, teams of graduate students have successfully completed sixty-three community-engaged projects for sixty distinct nonprofit organizations. I owe Roberta (Robbe) Healey, MBA, a Villanova faculty colleague and veteran nonprofit fundraiser, a debt of gratitude, as it was Robbe who first encouraged me to consider a hands-on project for the course during a Villanova Master of Public Administration (MPA) Advisory Board meeting. Since Fall 2011, the central student learning objectives for these projects have been outlined on the course syllabus: (1) to gain professional experience regarding the day-to-day work involved in nonprofit management and (2) to make a substantive contribution to the ongoing operations of a nonprofit organization.

While these learning objectives have remained the same over the years, this upcoming anniversary has allowed me to reflect on the evolving design and evaluation of community-engaged projects in my course and consider additional techniques so as to ensure an impactful experience for the partners involved (community, students, and faculty). Additionally, I am in the process of co-authoring a research paper with Dr. Stephanie Boddie, Assistant Professor of Church and Community Ministries at Baylor University, in how best to measure impact in community-engaged projects conducted at the graduate level.

The Value of Community Engagement

In order to appreciate the role and purpose of community-engaged projects, it is first essential to understand what community engagement is. According to the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, community engagement involves the “collaboration between institutions of higher education and their larger communities (local, regional/state, national, global) for the mutually beneficial exchange of knowledge and resources in a context of partnership and reciprocity.” As the definition implies, community engagement is a broader term than that of service learning as community engagement involves not only the realm of teaching and learning, but also a range of distinct, collaborative projects, initiatives, and research which aim for the mutual benefit of all its partners. Community engagement allows all partners to work alongside a variety of groups in public life with whom they might not otherwise come into contact. As such, community-engagement sharpens individual and communal points-of-view as well as provides opportunities for reciprocal learning.

Community-engaged teaching flows directly from this concept of community engagement. The Gephardt Institute for Civic and Community Engagement at Washington University in St. Louis outlines three core elements of community-engaged teaching: (1) faculty oversight of activities, projects, and student learning goals, (2) community voice in project development, and (3) course alignment with project and opportunities for student reflection. These three elements highlight the intended and mutually beneficial nature of community-engaged projects.

Community-Engaged Projects at Villanova – Stages of Development

Since the outset, in the Effective Nonprofit Management course community-engaged projects have involved three partners: (1) community partner (nonprofit organization), (2) student partners, and (3) faculty partner. The faculty partner approaches nonprofit organizations and invites them to consider serving as a project site for the semester, or nonprofits have contacted the faculty partner for project site consideration. In order to be approved as a project site, the faculty partner reviews the project title and short description which the nonprofit submits in advance of the class start date, as well as whether the project aligns with a topic covered in the Effective Nonprofit Management syllabus. Typically, community partners view the opportunity to work with graduate students favorably as it provides organizations with a team of graduate student consultants (at no cost!) who deliver a short, medium, or long-term project of interest to the community partner.

Prior to the Spring 2021 semester, the faculty partner selected the nonprofit organizations for which graduate students would be working as consultants during the course of the semester. The faculty partner did note, however, if graduate students were registered for the course from other Master’s programs, such as History and Theater, for instance, and made sure to include arts and culture organizations as project sites. After selecting the nonprofits, t he faculty partner developed a survey and asked all registered graduate students to rank their three top areas of interest, by nonprofit subfield and/or project type. These subfields and project types referred to the community-engaged projects conceived by the nonprofit organizations. After reviewing the rankings, the faculty partner would then assign students to the appropriate project by the second week of class.

This selection process changed in Spring 2021. The faculty partner now distributes a survey to registered graduate students ahead of the semester, asking them to rank their three top areas of nonprofit subfield interest. Then, the faculty partner selects nonprofit organizations in the Greater Philadelphia region for the community-engaged projects which align most with the nonprofit subfields of interest articulated by students.

After the team of graduate students is assembled, team members select a point person who serves as the primary communicator between the team and nonprofit. This designation of a point person builds continuity and trust by ensuring that there is always one graduate student speaking on behalf of the team to the community partner. Graduate students work in consulting teams throughout the semester and time is reserved during class for teams to meet to generate ideas, assign responsibilities, and ask the faculty partner questions.

Evolution of design and evaluation:

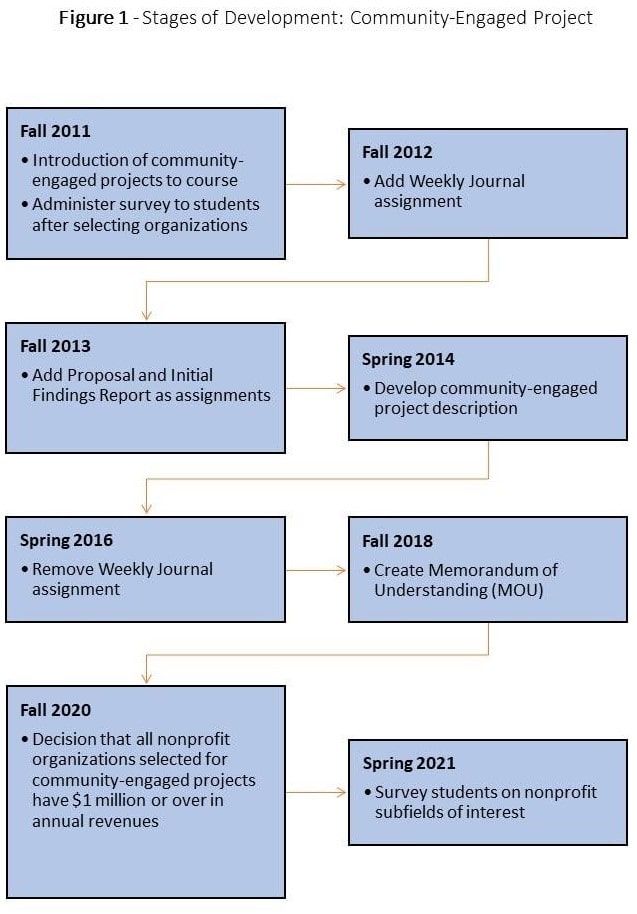

As Figure 1 demonstrates, the community-engaged projects in this course have undergone evolving design and evaluation over the last ten years.

This evolution in design and evaluation involves the following items:

- Fall 2011 – Community-engaged projects are introduced to course and students are provided with a survey to partner them with an appropriate nonprofit organization.

- Fall 2012 – A Weekly Journal assignment is added to syllabus so that students can document how many hours they are working weekly on the project. The project is designed in such a way that each student should be working 4-5 hours a week on the project.

- Fall 2013 – A Proposal and Initial Findings Report are added as graded course assignments to the syllabus in order that students can have multiple checkpoints with the professor before the submission of the Final Report.

- The Proposal requires students to outline their area of responsibility for the project and how that contributes to the overall community-engaged project developed by the nonprofit.

- The Initial Findings Report is an outline of the Final Project which is submitted by the student team which also points out student responsibility for each section of the project.

- The Proposal requires students to outline their area of responsibility for the project and how that contributes to the overall community-engaged project developed by the nonprofit.

- Spring 2014 – In response to a nonprofit request, the faculty partner creates a community-engaged project description that can be circulated to prospective community partners.

- Spring 2016 – The Weekly Journal assignment is removed from the syllabus as the faculty partner deems it to be unnecessary.

- Fall 2018 – The faculty partner develops a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) so that community, student, and faculty partners understand their roles and responsibilities. This MOU emphasizes the ongoing feedback that community partners should provide graduate student teams on the Proposal, Initial Findings Report, and presentation.

- Fall 2020 – In response to student feedback, the faculty partner decides to move away from having community/grassroots organizations as project sites due the lack of financial and nonfinancial data available to graduate students. The faculty partner selects organizations with $1 million or over in revenue for the community-engaged projects so that students have more data at their disposal to review.

- Spring 2021 – For the first time since the projects were introduced to the course, the faculty partner surveys registered students about their nonprofit subfield preferences before selecting organizations as project sites.

Nonprofit Subfields and Project Types

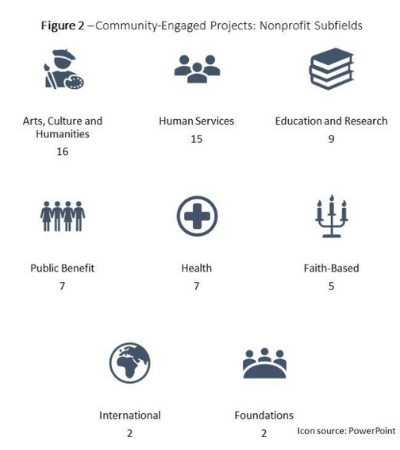

As mentioned above, in the Effective Nonprofit Management course, graduate students have successfully completed sixty-three community-engaged projects for sixty distinct nonprofit organizations. The community-engaged projects were grouped into categories (or subfields) utilizing an adapted version of Guidestar’s Directory of Charities and Nonprofit Organizations (see Figure 2).

The most common nonprofit subfields for community-engaged projects were arts, culture, and the humanities (16 in total), followed by human services (15). No community-engaged projects over the last ten years involved organizations in the environment or animal subfields. In addition, two projects were developed by private foundations, which do not fit into any of the nonprofit subfields identified on the Guidestar list. The most sought-after projects by nonprofit organizations were a marketing and communications plan (18 in total), followed by a strategic plan (8), a community engagement or outreach plan (7), and fundraising plan (5). Other types of projects were unique to the nonprofit and not easily grouped into categories, such as, a consumer lending program, service-learning project, and mentoring project, among others.

Evolving design and evaluation:

I plan to continue to administer the survey to graduate students in advance of class to ascertain the nonprofit subfields in which they would be most interested in for the community-engaged projects. Given that Spring 2021 was the first semester in distributing these surveys in advance of class, I anticipate that we will have more representation from the animal and environment subfields for community-engaged projects in the future. An important caveat to Spring 2021 – the animal subfield was ranked as a top area of interest of students, however, while two animal welfare nonprofits voiced interest in participating in a community-engaged project that semester, they simply did not have the capacity to do so. These organizations asked to be considered for an upcoming semester.

Situating Oneself in the Work

In Fall 2020, I delivered a virtual presentation on a panel entitled “Navigating Dynamics in Community-Engaged Research and Practice” at the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action (ARNOVA) conference. In preparation for the panel, Dr. Margaret Post, research assistant professor at Clark University, encouraged panelists to discuss how they situated themselves in community-engaged projects. This was such an invaluable experience and provided me with the opportunity to examine the two main reasons why community-engaged work continues to inspire me: (1) the importance of community voice and (2) the role of the unexpected.

- Importance of Community Voice – Many community-engaged projects feature organizations and initiatives which assist populations who are misunderstood, forgotten, and voiceless. My interest in this work stems from my research in Latin American Studies and of Hispanic communities in the United States. I have always been intrigued by what we can learn from other cultures and how we can build bridges of healing, insight, and innovation within and among different cultures. Furthermore, I have benefited greatly from actively listening to communities and cultures unlike me, to engage in a respectful exchange of ideas, and to find common ground amidst differences. These exercises have enabled me to check and challenge any preconceived ideas I might bring with me to the table, either in teaching or research.

- Role of the Unexpected – As a qualitative and ethnographic researcher, I have realized how important it is for individuals and communities to speak for themselves and on their own terms. Ethnographic research is not always predictable and does not conform easily to insights contained within scholarly literature. Community-engaged projects are similar in this way; while much important literature has been published as to the value of these projects and the range of learning outcomes obtained in this work, each project brings its own level of complexity given that individual organizations are involved. And these nonprofits each have their own organizational cultures and leadership styles which shape the nature of the relationship forged between the community, student, and faculty partners.

Evolving Design and Evaluation:

Understanding the faculty partner’s motivations for involvement in community-engaged projects is an important feature of implementing these projects in a semester-based course. It is important to note, however, that while students taking an Effective Nonprofit Management course most likely will share in the faculty partner’s interest in valuing community voice, they may not register the same level of enthusiasm for the unexpected turns a community-engaged project can take. Students must be reassured throughout the course of the semester that while they have received the blueprint for the project, the project may not follow the plan exactly as they anticipated – i.e., personnel changes may take place at the nonprofit, shifting responsibility to another nonprofit leader; students may not hear back from the nonprofit leader in a timely manner or in an expected timeframe; and/or certain graduate students may not have a strong working chemistry with other members of their team. Here, the faculty partner must step in to mitigate some of these uncertainties, reinforcing to students that learning new ways to respond to unforeseen and challenging circumstances is a key component of personal and professional growth.

Lessons Learned

There are several key lessons that I have learned from overseeing these community-engaged projects over the last ten years in my graduate class, which I outline below:

- Secure and nurture community input – This is the foundational element in designing a community-engaged project which serves to benefit the nonprofit organization and the constituents they serve. In addition to focusing on student learning outcomes, successful community-engaged projects secure community input at the outset and nurture this input throughout the semester. Faculty partners can secure input by providing a range of options (aligned with topics covered in the syllabus) from which community partners can choose in their design of the community-engaged projects. Having nonprofit input as the project’s foundation truly guarantees that the project is indeed a community-engaged one and bolsters an active participation in the project by community partners. Faculty partners can nurture input by requiring students to have multiple check-ins with their community partner, i.e., feedback on the proposal, initial findings report, and presentation.

- Reaffirm student learning objectives – Faculty partners should regularly reaffirm the particular learning objectives that community-engaged projects provide to students. This is especially the case since faculty may have students in their course who may be acting as consultants for a project for the first time in their academic career. Faculty partners should clearly outline these learning objectives not only in the syllabus, but also regularly during class time, breakout sessions, as well as in student team meetings with the faculty partner. Faculty partners should also listen closely to student feedback (e.g., choosing larger-sized nonprofit organizations) in course evaluation forms and other types of surveys and adjust community-engaged projects in ways that might better benefit student learning objectives.

- Outline clear roles and responsibilities – There is great need for consistent faculty oversight of community-engaged projects to ensure that all partners are in agreement regarding the scope of the project and that key deliverables are being met. The best way to ensure this agreement is by sending all partners a memorandum of understanding (MOU) which outlines the roles and responsibilities of each partner. Faculty partners should adopt the role as a “conductor” of these projects, overseeing the harmonious delivery of all of the project parts; encouraging students to divide the project into sections which best align with their individual strengths; and distancing themselves from taking the project into directions that might be of interest to the faculty partner, but not the community partner. As a conductor, it is oftentimes the case that faculty partners need to step in to narrow the focus of the project and/or allay student fears of viewing the project as something that is insurmountable.

- Schedule regular student-community-faculty check-ins – Faculty partners should build into the syllabus multiple check-ins which enable student teams to communicate their ongoing progress to community partners. This can take the part of graded assignments whereby students receive faculty commentary and then send the revised assignment to the community partner for their review and approval. In addition to scheduling time with the community partner at the outset of the semester, student teams should strive to meet with community partners at least once or twice throughout the semester to review their feedback. Faculty partners should meet at least once or twice with student teams to answer questions, address challenges, and provide helpful resources. Finally, apart from the initial conversation regarding the nature and scope of the project, faculty and community partners should schedule time during mid-semester to discuss the progress of the student team and any need to redirect the team on the project.

Evolving Design and Evaluation:

- Build in relevant content – In revisiting the purpose of community-engaged teaching, I plan to include in future syllabi readings that provide students with the opportunity to grapple with the role and purpose of community-engaged projects in a graduate nonprofit management course. Inclusion of these readings will aid in bridging the gap in the course between current readings on nonprofit management and student involvement in community-engaged projects. The Gephardt Institute for Civic and Community Engagement at Washington University in St. Louis has a helpful checklist of items to consider when planning a course with a community-engaged feature.

- Set aside time for self-reflection – Self-reflection – for student, community, and faculty partners – should be a central characteristic in the evaluation of community-engaged projects. The Institute for Civic and Community Engagement at San Francisco State University lists ways that this reflection, or “critical analysis,” can be integrated into the course, such as through creative writing or class discussions. I intend to set aside time for self-reflection for all partners in future course offerings (through group discussions and/or surveys) so that partners have an opportunity to process the kind of learning that has occurred and make recommendations for future projects.

- Measure levels of impact – Community-engaged projects should not be designed simply to advance student learning objectives, but – as Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching argues – to further “community action goals.” And, faculty partner learning is also an important part of the equation. Thus, in future semesters, I plan to adopt a multidimensional assessment, with an emphasis on how involvement in and completion of these projects have impacted student, community, and faculty partners in a range of ways. This assessment will allow the faculty partner to have a greater sense as to the varied effect that community-engaged projects have on the three distinct types of partners. Furthermore, it will allow the faculty partner to move away from the “check the box” phenomenon, i.e., equating a successful project with one that is completed and delivered to the nonprofit organization.

- As an educator at the undergraduate or graduate level, consider adding a community-engaged project to your course, whether as a short-term project (i.e., for a few weeks) or for the duration of the semester. Such a project could help enhance the skills, competencies, and civic engagement of student partners, provide vital assistance to community partners, and strengthen the management skills of faculty partners.

- As a leader or manager in a nonprofit organization, consider partnering with a college or university to have a team of students develop a community-engaged project on an area of strategic interest and for which it may be difficult for paid staff to set aside time. Community-engaged projects have a well-defined outcome, i.e., a short, medium or long-term project successfully completed. Additionally, these projects have additional positive long -term outcomes, including relationship-building with a higher education institution in the region.

- Read GrantStation’s interview with Dr. Wilson, The Measurable Impact of Community Engaged Work