The Gospel of Giving of America’s First Female Self-Made Millionaire

Coming from humble beginnings often prefaces the stories of highly successful people, but few rags to riches tales begin in more meager circumstances than those of Sarah Breedlove. She was born just after the end of the U.S. Civil War, in 1867, in the federally partitioned U.S. south, in the Fifth Military District encompassing Louisiana. It was a time of soaring hopes for African Americans, but southerners soon began fighting back against Black emancipation, principally by erecting the apartheid regime known as Jim Crow, slowly expanding racist laws until nearly every avenue toward equality was blocked. It was in this reality that Breedlove came of age.

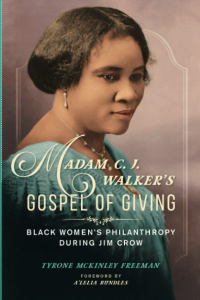

Despite this, she built a beauty products empire, employed thousands of sales agents nationwide, became the first documented female self-made millionaire, and used much of the resulting fortune for philanthropy. Today she's well known in the annals of Black and post-Civil War history, and even has lengthy Wikipedia and History.com entries under the moniker she adopted—Madam C.J. Walker. But aspects of her story had never been told until recently, when Tyrone McKinley Freeman, Assistant Professor of Philanthropic Studies at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, published the new biography Madam C.J. Walker's Gospel of Giving.

Freeman is always busy with his academic work, but is accommodating about taking time to discuss his book. We communicated by email and phone. As befits an academic, his written comments are extensive and exacting. By phone he's upbeat and laughs easily, even though our conversation takes place during the most humorless hours of the recent U.S. presidential election, when counts are dragging on and political squabbles are playing out across the nation.

But there's something fitting about it too. Voting is, in its ideal form, a community duty, and Madam C.J. Walker's Gospel of Giving talks about both community and duty a lot. Freeman takes pains in the book to highlight Madam Walker's strong connections to the places she lived, both in her native south, and in regions farther west and north to which she migrated trying to escape racism. “She was raised in churches and benevolent societies among working Black women,” he explains, “and followed traditions of engagement and giving that had been established within African American communities before she was born, and practiced by generations of Black women who came before her.”

“I place Madam Walker within the context of her peers,” Freeman continues, “which is very important. Because she became a millionaire, we tend to separate her in our imagination from others. While achieving such extraordinary success was a testament to her relentless pursuit of a dream, and says much about her own character and nature, we must remember that she came out of many networks of Black women. I believe she was deeply shaped by the washerwomen, churchwomen, clubwomen, and other educators and activists who both supported her and with whom she worked alongside to meet local community needs and challenge the system of Jim Crow.”

“Walker's gift giving, like herself, had humble beginnings.”

Walker's gift giving, like herself, had humble beginnings. She sometimes merely waived the fees her sales agents were required to pay in order to purchase an inventory of her beauty products. While these weren't cash disbursals, they allowed her agents to start earning money right away through their own work. She also helped relatives, in one case providing her sister the resources to secure a son's release from prison. Freeman notes that while white Western models of philanthropy involved giving to strangers, in the African American tradition aid often went to family members. In a country hostile to Black aspirations, such support within family networks was indispensable.

“No matter how much money or status Madam Walker attained she was still Black,” Freeman explains, “still female in Jim Crow America. At any moment, she could have been lynched or raped. So, no matter her achievement, she needed just as much liberation as the millions of penniless Black migrants who like her moved out of the south to the north and west under the threat of Jim Crow.” This is an essential point made throughout Freeman's narrative. Walker, while rich, could not truly be a member of the wealthy elite. The dangers of life during Jim Crow were never far from her doorstep. The Equal Justice Initiative conducted a study showing that more than 2,000 Blacks were murdered extra-judicially between 1865 and 1877—more than 160 each year. Walker was ten years old in 1877, and these killings would have placed an indelible stamp on her childhood. Subsequently, resisting Jim Crow became central to how she shaped her philanthropy.

Madam C.J. Walker's Gospel of Giving serves as not only a biography, but as a history text that illuminates the Jim Crow system. Most Americans know what Jim Crow was, but rarely understand it as a constantly changing, infinitely adaptable system, in place for almost a century, serving the desires of racists dedicated to stymying Black progress. As Freeman puts it, “The legal, social, political, and economic landscape was focused on holding back Black success and achievement. Walker was not supposed to be successful. She was not supposed to be providing opportunities for Black people. She was supposed to stay in her place. Jim Crow intentionally made everyday life difficult for Black people. That was its design. Walker harnessed her own generosity and combined it with that of others to push back against this system, while expressing their own deep humanity and dignity in the process.”

Walker's philanthropy grew in scope as her beauty empire expanded. She gave baskets of food during the holidays, and in one highly individualized instance of giving bought a disabled man who hadn't left his home in eighteen years a “wheeling chair.” At the height of her success she began making large gifts. Though the term “nonprofit” didn't really exist during her time, she provided important assistance to early Black nonprofits, or social service agencies. This was crucial because most white-led nonprofits would not accept Black clientele. Numerous orphanages and old folks’ homes were whites only. Blacks were forced to create and fund their own organizations for such purposes, and Walker was able to help. In 1911 she gave the Black YMCA in Indianapolis $1,000 (about $28,000 in today's money), and in 1919 she was the source of what was at that time the largest donation the NAACP had ever received, $5,000 to the group's Anti-Lynching Fund. She also funded scholarships for women at the Tuskegee Institute, and at one point envisioned building a Tuskegee Institute in Africa. All this from the most humble beginnings, and in an era of intense hostility toward her goals.

Madam C.J. Walker's Gospel of Giving also discusses personal setbacks, family challenges, and professional relationships, all of this steeped in the realities of late nineteenth and early twentieth century America. Ultimately the book paints a portrait of a unique historical figure, but also contains food for thought for today's nonprofit leaders and employees. Walker's connection to her various communities, and particularly her dedication to interacting with them as a peer, highlights the issue of diversity in nonprofit staffing.

“Walker was not supposed to be successful. She was not supposed to be providing opportunities for Black people.”

I asked Freeman his thoughts about it and he pointed out that, “Walker gave gifts that she herself needed and benefitted from early in her life. She knew poverty, lack of education, and struggles in caring for her child. I do believe grantmaking organizations benefit when populated by people who have proximity to the issues being addressed through the funding, but only when the presence, perspectives, and voices of those with proximity are taken seriously to reshape institutions and the ways they do their work.”

He also noted that staffing is only one part. “For decades, groups like ABFE (Association of Black Foundation Executives) and others have advocated for more equitable grantmaking practices, including representation and voting power for recipients from the community, longer term grant cycles over multiple years, even decades, rather than one- or two-year grants, and, more recently, funding nontraditional groups that are on the leading edge of change. So, I think it will take a range of approaches to truly get to where the field needs to be and to truly respond to what communities need and to what social change processes demand.”

Freeman says that the response to his book has been good so far. In recent weeks he has given talks to groups of professionals, philanthropic giving circles, and a church congregation. Before he began the monumental task of piecing together Walker's life from more than 40,000 historical documents, he created a sort of avatar to guide him, a thirty-something African American woman caring for her own family while active in her community. “I participated in scholarly conferences in philanthropy, history, and Africana Studies to interact with philanthropy scholars and historians of Black women in order to develop the frameworks necessary for analyzing and understanding Walker as a giver on her own terms, and Black women, more broadly, by extension.” While he wrote with his avatar in mind, he hoped the book's audience would be broad, and on that score, early indications have exceeded his hopes.

“There’s something in the book for everyone. Fundraising and advancement leaders can gain greater knowledge and understanding of how philanthropy works within communities of color, which they can then use to inform their efforts to build trust and engage with donors of color more effectively. Grantmakers can learn more about how the dynamics of power and philanthropy have played out when enacted upon Black communities from outside, and how those communities’ own internal cultures of generosity have not only shaped their responses to such oppression, but expressed and represented their own deep humanity and dignity.

“Other nonprofit professionals like program directors, educators, and social service providers will see Madam Walker active in their own spaces and making a difference with relatively little compared to the scale and scope of the social programs she faced (which these professionals know a lot about, too). Also, Walker was on the front lines of the leading social movements of her day, such as anti-lynching (the antecedent to today’s Black Lives Matter movement), temperance, and women’s suffrage. So, activists will find engaging stories and information in the book from which they can hopefully draw inspiration and refuel as they continue doing the hard physical and emotional work of social change.

“…philanthropy does not generate from wealth, it comes from generosity.”

“I hope that people will unlearn the idea that philanthropy belongs solely to the wealthy elite,” Freeman says, “and that they cannot do anything meaningful or helpful for others because they might not have a lot of money to give away. Madam Walker’s gospel of giving is an accessible form of philanthropy, available to the rest of us, which says anyone can be a philanthropist because anyone can give from what they have at any particular moment. So, the most important idea I hope readers take away is that philanthropy does not generate from wealth, it comes from generosity. We do not have to wait to give, be helpful to others, or challenge systems. We can start right now. And as we acquire more, we can do more.”

Tyrone McKinley Freeman, Ph.D.

Tyrone McKinley Freeman, Ph.D.

Tyrone McKinley Freeman’s work examines African American philanthropic agency in historical and contemporary contexts with an emphasis on the ways in which African Americans have used philanthropy to express their dignity and humanity as well as to survive and press for massive social reform.

He is assistant professor of philanthropic studies and director of undergraduate programs at the Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at IUPUI.

Tyrone is a proud HBCU graduate, having earned his B.A. in English/Liberal Arts from Lincoln University (PA). He earned a master’s in urban planning from Ball State University, a M.S. in Adult Education and Ph.D. in Philanthropic Studies from Indiana University.

Follow him @mckinleytyrone