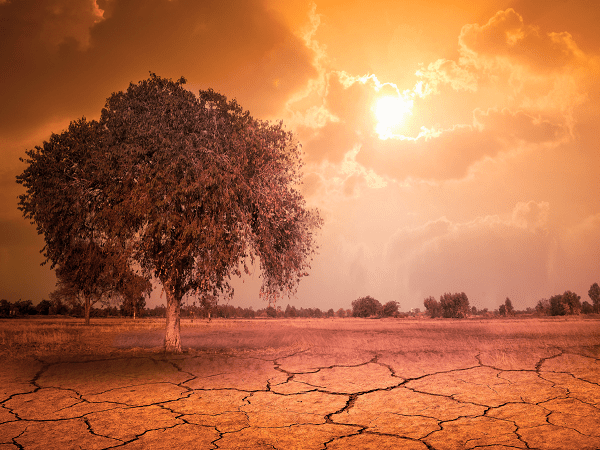

There's a meme based on the television cartoon The Simpsons in which 10-year-old Bart anguishes, “This is the hottest summer of my life.” Homer suddenly appears to tell him, “This is the coldest summer of the rest of your life.” It qualifies as gallows humor, because July was the hottest month ever recorded and August and September broke heat records for those months, despite all the warnings about climate change and all the promises made and political posturing by governments. While each of the UN's Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is important, SDG 13, Climate Action, stands at the center of hopes for a prosperous and green future. All the difficulties, paradoxes, political obstacles, and moral imperatives are positioned there too, making it possibly the most urgent challenge humanity has ever faced.

The UN is asking, by 2030, for “deep, rapid, and sustained emissions reductions” to avoid catastrophic global overheating. The number most often cited is 1.5° Celsius, which is 2.7° Fahrenheit. That's the level of heating above which scientists estimate humanity will be routinely afflicted by dangerous climate effects that radically alter human existence. These include deadly heatwaves, rampant wildfires, flooding of inland areas as well as coasts, stronger hurricanes, and a rise in infectious disease transmission, all bringing immeasurable economic costs. Along for the ride will come irreparable damage to the ecology, including coral reef death and species extinction. However, on current trends, not only is the world on track to blow past 1.5°C by the year 2100, but 3°C is in play. What's in store if emissions hit that level? Disaster movie scenarios—everything from inundated coasts to the unchecked movement of billions of climate refugees.

These scenarios must be avoided, but unless the public understands the risks, political will is unlikely to galvanize in time. According to a Pew Research Center survey earlier this year, only 37% of Americans want climate change to be a top government priority. It ranked 17th of 21 issues measured, far behind “strengthening the economy,” and just after “strengthening the military.” When one considers that economic losses are baked into climate change and the U.S. military by itself consumes and emits more carbon than most countries, it's easy to see the contradictions inherent in the public perception of climate breakdown.

Last year only about 1.5% of charitable donations went toward climate change mitigation, and that small total represented a substantial jump over recent years, thanks mainly to large foundations, new foundations, and younger donors. The number of nonprofits that received climate-related funding rose from 1,400 eight years ago to 2,775 last year, and the total money directed toward the problem was somewhere around $8 billion, according to some estimates. While the increase in donations is welcome, up to $9 trillion dollars will need to be leveraged to tackle the problem. That's literally more than one thousand times more dollars than at present. Need of that immensity makes coordinated, international government action mandatory.

In the political realm there's been finger pointing about emissions. In reality, all major countries bear responsibility. In 2022, China approved an average of two new coal power plants each week. This boom occurred due to three major factors: new demands for air conditioning during summer heat waves, high natural gas prices due to Russia's invasion of Ukraine, and a shortage of hydroelectric power because of drying rivers. The feedback loops created by opening new coal plants ensures that demand for cooling will rise even more. China has pledged that its emissions will peak in 2030, but how high will they go before that point?

While the United States is shifting away from coal, since 2011 it has been the world’s top producer of natural gas, and since 2018 has been the top producer of oil. It is also the planet's largest historical emitter, having pumped more carbon-trapping gases into the atmosphere than any other nation. The U.S. and China alone produce 42% of all global emissions. Competition between the two nations makes climate solutions difficult. Reaching consensus between competing economies, opposing geopolitical interests, and different visions for the shape of future global order present tremendous obstacles to simply doing what is right. Even so, the U.S. has managed to contribute more than most countries to the UN's Green Climate Fund.

Other high emitting countries, such as Brazil, Russia, Mexico, Indonesia, Germany, India, and the U.K., have their particulars, but in every country reducing emissions necessarily means cutting public and private consumption. In democratic environments, this sets up opposition between political campaigners who are pragmatic with prospective voters, versus those who claim few if any limits are needed and people can consume according to their desires. The truth, then, becomes an attack on lifestyle. As politics now stand, politicians who tell voters that they cannot have what they want usually lose elections.

There's an added complication when the problem is viewed from outside the West. Then, politicians must tell their public not only that they can't have what they want, but that they can't have what Westerners have long had and take for granted. Essentially, they can't have the huge SUVs, flatscreen televisions, expansive centrally cooled houses, unlimited flights to overseas cities, and other exotic luxuries they've learned to covet thanks to Western media, because the West has used them up. They, not Westerners, must sacrifice in order to stop global overheating. It's difficult to imagine a more losing political formula.

When interviewed by journalist Christian Lusakueno last year, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken admitted to the imbalance between Western consumption and what is being asked of non-Western countries: “We’re the number two polluter,” he said of the United States. “But historically, also what we did for our own development, we did things that we are asking other countries not to do today. So it’s normal that countries will tell us, well, you exploited your forests [but] we are asking you not to do this. So it’s entirely normal and appropriate.”

His words struck a conciliatory tone, but in opposition to the UN's climate goals stands—among many other entities—a Republican-controlled House of Representatives, which routinely blocks climate action. Looking to the future, the powerful Heritage Foundation has already drawn up a blueprint for the next Republican presidency, titled Mandate for Leadership, that calls for across-the-board dismantling of federal oversight bodies, including stripping the Environmental Protection Agency of any climate powers. Leading Republican presidential candidates are in agreement that climate change, or sometimes “the agenda of climate change,” are hoaxes.

Yet another problem is that developing nations feel diminished by Western approaches to the issue. The first Africa Climate Summit took place last month and was dominated by Western organizations and voices. One would think African emissions were a crucial piece of the climate puzzle, but the continent produces only 2% to 4% of global carbon emissions. However, it disproportionately suffers from global overheating in the form of floods, drought, famine, and climate exacerbated conflict. Ugandan climate campaigner Vanessa Nakate said of Western dominance of the Africa Climate Summit, “We want solutions that are led by African people, for African people, on African terms.”

Some smaller nations have taken an approach to raising their voices that could have repercussions upon the global balance of power. The island nation of Vanuatu, backed by 1,500 civil society groups and sponsored by 130 other countries, demanded clarity earlier this year from the International Court of Justice on the rights of present and future generations. It was the first such case to reach the court and could herald a wave of climate litigation (though neither the U.S. nor China recognize the court's authority). Meanwhile, a lawsuit by Bahamas, Tuvalu, Vanuatu, and other countries was heard by the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) last month, a body with 168 signatory nations (though not the U.S. or Iran). Lead counsel in the ITLOS lawsuit Payam Akhavan explained, “What’s the difference between having a toxic chimney spewing across a border [and] carbon dioxide emissions?”

Because of the many crosscurrents surrounding the issue, to some climate advocates the UN has legitimacy problems. The organization has allowed the United Arab Emirates to host the upcoming United Nations Climate Change Conference, also known as Cop28, and polluters are some of the event's largest sponsors. Writing in The Guardian, climate expert Bill McGuire compared UAE hosting Cop28 to “a big tobacco CEO hosting a cancer conference.” It's indeed difficult to believe petrostates want to do anything other than delay a shift away from oil. UAE is currently planning a massive expansion of oil and gas production, third highest globally after Saudi Arabia and Qatar. Climate experts estimate that 90% of that material would need to remain in the ground in order for SDG 13 to be achieved.

The SDGs, their drafters would probably say, are clear about trying to form partnerships, and those would necessarily include working with carbon emitters. A stance that alienates producers of some of the most profitable substances in existence is destined to fail simply due to an imbalance of economic and geopolitical power. But the problem may be that partnerships asking fossil fuel states to “dance on two dance floors at once,” as ex-UN climate head Christiana Figueres put it earlier this year, are possibly destined to fail anyway, greatly costing future generations.

The back and forth analysis of the issue can go on, but the upshot is that in order to avoid the worst effects of global overheating, industrialized nations need to cut emissions in half by 2030 and stop adding carbon dioxide to the atmosphere entirely by about 2050. In order to achieve this, as prices currently stand, about $100 trillion worth of underground assets need to be left unextracted. That's an unimaginable figure, representing a level of profit that by itself explains why there is such powerful and organized resistance to change.

Yet hard science shows that SDG 13 can be achieved. Chemistry, physics, and engineering all agree that the tools exist. The social science of economics agrees that the costs of doing nothing will be greater tomorrow than any savings gained by delays today. The obstacle is politics. Politics change when culture changes, culture changes when people clearly perceive a problem, and this is where civil society plays a key role. It's often the nonprofit sector that helps shift public thought. Even nonprofits that aren't specifically climate focused can help effect change. Groups ranging from UNICEF to Global Fund for Women have missions that tangentially impact climate. Nearly every nonprofit can contribute in one way or another, and with concerted and collective effort, any achievement is possible.

- Download the Sustainable Development Goals 2023 report.

- Read more articles in this series about the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.