Homelessness is a persistent problem in the U.S., one that has ripple effects into many areas targeted by nonprofits, from drug addiction to sex trafficking. The Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) issued a 2020 report on the subject that put the number of Americans experiencing homelessness on a given night at more than 580,000. For this population, life would be even more challenging without social service organizations stepping into the breach to offer aid and assistance, but the work of those organizations could become more difficult if ongoing trends around homelessness continue on their current course.

The first item to note is that the OECD's figure, while shocking, is probably not accurate. The actual number is thought by many experts to be at least twice as high, and current nationwide estimates of homelessness were released in early 2020, but calculated from data collected in 2019, before COVID-19 was declared a health emergency. The impacts of the pandemic haven't been measured everywhere, and won't be precisely known until sometime in 2022, but some cities have begun to assess the damage. A mid-October report by UNC Charlotte’s Urban Institute and Mecklenburg County revealed that homelessness in the region skyrocketed by 55% over the last year. This increase may prove typical in medium to large cities across the U.S., exacerbated by factors such as the end of eviction moratoriums and sharply rising rent costs.

Homelessness had been trending downward modestly between 2007 and 2018, largely due to efforts targeting the problem among military veterans and families with children. For the first group the decline since 2007 had been 39%, and for the second it was 27%. Some of the progress of those years has undoubtedly been wiped out. The U.S. public certainly gives indications it thinks the problem is worsening. In a March 2021 Gallup poll, hunger and homelessness was a top social concern for 55% of respondents, the most since polling on subject began. The increase was likely driven by visible homelessness soaring during the pandemic.

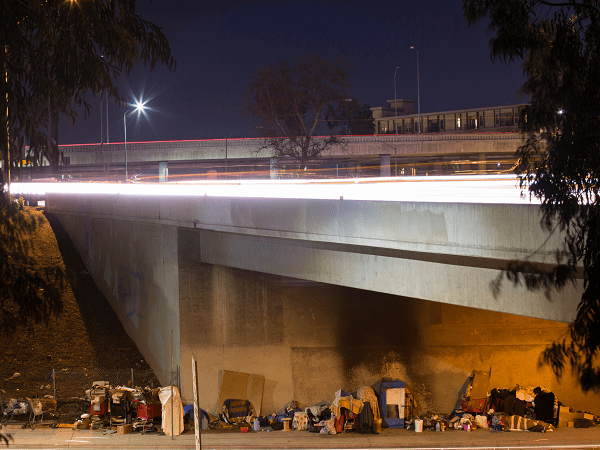

With more visibility also comes less patience. A recent poll in Portland revealed that 61% of metro area residents favored simply forcing individuals without homes out of downtown. Meanwhile in Denver, an aggressive new proposition would not only require the city to dismantle homeless encampments within three days, but also face potential lawsuits from property owners if it failed to abide by the law. The three-day deadline directly contradicts federal statutes, but that's the tug-of-war the issue has become: nonprofits are often utilizing federal funds to tackle the problem even as city councils and state government undermine their efforts.

Forecasts for the immediate future are not sunny. In September, a Goldman Sachs analysis suggested that 750,000 U.S. households could be evicted across the United States before the end of 2021. Its estimate attempts to predict the aftereffects of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling against eviction moratoriums. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) had determined that allowing people to remain in their homes instead of being thrown into crowded living conditions or homelessness would help mitigate the spread of COVID-19, but the moratorium officially ended on August 26. At that time, the credit rating agency Moody's estimated that approximately 7 million households were behind on their rent, collectively owing $21 billion to landlords and utility companies. The number represented 15% of renter households nationwide.

Though the CDC order has been quashed, eviction moratoriums are still holding steady in a few important places. New York City's will extend through the end of the year, and Boston's is also ongoing. Meanwhile, some areas where moratoriums did end have seen lower-than-expected eviction rate rises because landlords are barred from taking action against renters who are awaiting decisions on applications for federal rental assistance, while other landlords have decided, either on their own initiative or advised by landlord advocacy groups, that waiting is the best decision. But as the year draws to a close more property owners will either run out of patience or be forced into action due to financial need.

Some landlords are quite happy to evict tenants. The end of COVID-19 moratoriums means that some—particularly corporate ownership groups—are eager to raise rent once their properties have been cleared. As noted at top, rent costs are rising precipitously across the United States. COVID-19 struck amid what was already an affordable housing shortage. Against that backdrop, rents have climbed by double digit percentages in the last year in cities as geographically diverse as Las Vegas (42%), Boise (40%), Winston-Salem (23%), and Jacksonville, (35.5%). Increases across Florida as a whole have been averaging 22.6% per year. Among the country's 100 largest metro areas, rents have risen in all of them during the last five months.

The timing of rent spikes is unfortunate. According to the nonprofit National Low Income Housing Coalition, no U.S. state has an adequate inventory of affordable housing for the poorest renters, who are defined as having incomes at or below the poverty line, or at 30% of median income within a geographical area. The problem is particularly acute in places like Los Angeles, where the unhoused population increased 16% from 2019 to 2020 to 41,290 people. This is the inhospitable landscape nonprofits face.

In addition, some homelessness nonprofits have closed since the advent of COVID-19, leaving workers who remain in the field stretched thinner than ever at a time of increased need. It's worth noting, as well, that on the subject of strain, average pay for the 60,000 full- and part-time nonprofit staff performing this crucial work across the United States is $24,000 per year. Many have moved on, unable to survive on the low earnings. As year-end fundraising kicks into high gear, nonprofits that work in and around the homelessness issue will try to factor rising need throughout 2022 into their plans if they're able, but many are trying to simply recover from COVID-related funding woes. Washington, D.C., for example, facing a $200 million budget shortfall in 2020, pulled back support for local homelessness nonprofits during the height of the pandemic.

The news isn't all bad. Many metropolitan areas are trying fresh ideas. Seattle purchased seven hotels and an apartment building with money from a new sales tax, with the goal of permanently housing 1,600 people. Los Angeles, in partnership with nonprofits such as The People Concern, launched a bridge housing initiative that aimed to provide temporary shelter for thousands, offering a foothold before transitioning into permanent housing. In San Francisco, a pilot program called Miracle Money gave no-strings $500 monthly payments to a dozen people without homes. Half the participants obtained stable housing. Oakland launched a much larger effort called Oakland Resilient Families. Put together by the nonprofit Family Independence Initiative and Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, the initiative has been giving $500 a month to six hundred low-income families and will do so for eighteen months. Another guaranteed income experiment in Stockton found that cash gifts not only resulted in more full-time employment, but benefited recipient families’ physical and emotional health.

Innovation is always an aspiration, but what many nonprofits really want is more no-strings-attached funding themselves. Most organizations know from experience which solutions work best and seek the financial capability to pursue those courses of action. There has been help from the federal government. The American Rescue Plan passed in March included $40 billion for rental assistance and homelessness. The Build Back Better Act contains homelessness provisions, but those face excision from what will be a drastically hollowed out final piece of legislation. There's also a federal initiative called House America, unveiled six weeks after the Supreme Court ruled against eviction moratoriums, that asks leaders of city, county, state, and tribal governments to tackle homelessness in exchange for guidance and support. The two-pronged goal is to provide permanent housing for those who lack it, and to build affordable housing so that renters have more options on the market, but passage and implementation would have to come against Republican opposition.

Generally, the debate over what to do about homelessness is fought between those who describe it as a personal failing not deserving of strong, coordinated intervention, and those who actually study its causes and understand that in reality it's brought about by choices made in the U.S. around mental health, law enforcement, workers' wages, racial equality, and housing markets. Putting a serious dent in the problem is possible, according to most experts, but only by viewing it as the systemic failure it truly is. Nonprofits across the social services spectrum face a challenging upcoming year, but maybe, with an abundance of fresh proof that the current increase in homelessness is linked with COVID-19 and the problems it unleashed or made worse, a greater willingness to examine the issue more objectively will follow.